Climbing is a great game; great not in spite of the demands it makes, but because of them. Great because it will not let us give half of ourselves, it demands all of us. It demands our best. – Royal Robbins

If the 60s and 70s are consider the Golden Age of rock climbing then Yosemite Valley was the place to be and Royal Robbins was one its masters, and its most ardent guardian. Robbins died last week at the age of 82.

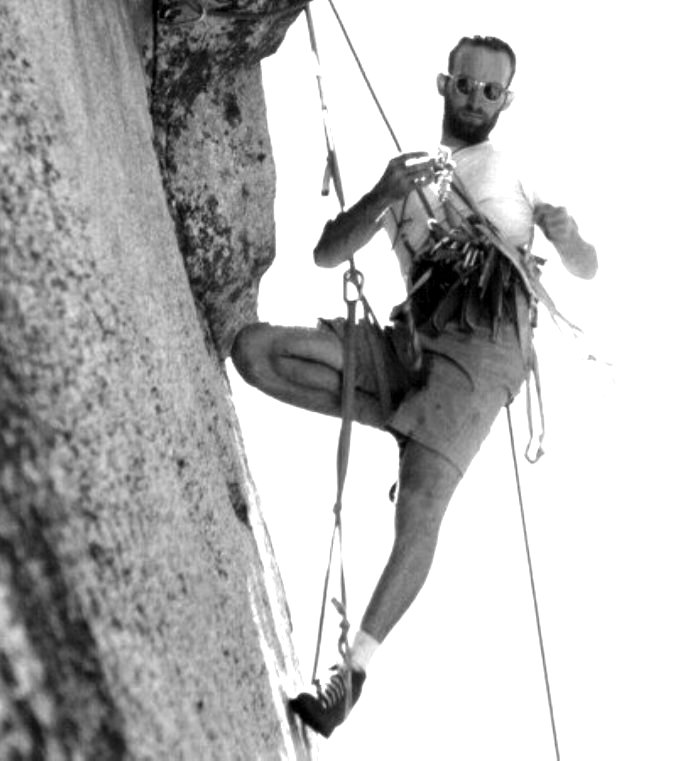

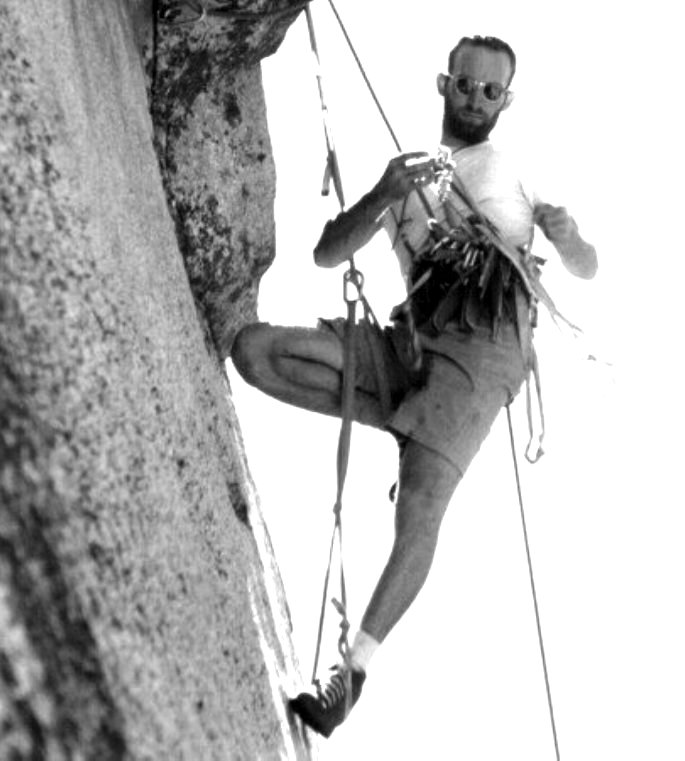

Here he is leading the third pitch (third section of a climb), on the “Salathé Wall” of El Capitan.

“Rock climbing is a game of rules,” Outside Magazine writes (Mar. 15). “It has no meaning without arbitrary limits on the use of gear—drilling bolts, not drilling bolts, hanging ropes from above—and shared agreement about what constitutes a great achievement. Nobody in the history of North American rock climbing did more to define those rules, and the culture of climbing today, than Royal Robbins…

“Put another way, every man and woman who currently climbs outdoors, regardless of whether or not they’ve heard of the guy, lives in a world that Royal Robbins created.”

I was one of those climbers. I climbed in the early 70s: Joshua Tree, Stony Point, Mt. Whitney, and several other places whose names I can’t remember. This was before climbing gyms and free climbers. I became so interested, I wanted to make a film about it, an ultimately did at Suicide Rock (sounds more imposing than it actually was), in Idyllwild, California .

I read everything I could get my hands on; talked to climbers, and most everyone I spoke with always spoke – with reverence – about Royal Robbins, not only because he was a climbing god, but because he believed in ethical rules about climbing.

“Robbins,” The New York Times writes (Mar. 15), “became part of the sport’s consciousness, a powerful advocate for clean climbing, urging those who followed him up the rocks to leave few traces of their path. …

“Daniel Duane, who has written three books on climbing, including one on Robbins, told The Associated Press. ‘The lives of those of us who climbed were enriched by Royal’s insistence on getting the rules right. If it hadn’t been for Royal, all those cliffs would be a total mess.’ ”

“Robbins,” Outside continues, “learned to climb in the early 1950s at a granite crag called Tahquitz, outside Los Angeles, and immediately established a pattern of audacious bravery. First, at the age of 17, Robbins tackled the then-infamous Open Book, the first multipitch 5.9-rated climb in the United States, which had been climbed for the first time only one year before with the use of so-called direct aid, meaning those original climbers hammered gear into the cliff—2×4 lumber, as it happened—then attached stirrups to that lumber and stepped into the stirrups to make upward progress.”

Robbins, however, would change all of that. He, along with Yvon Chouinard, created the next level of climbing equipment. Used by the leader (first climber on the rope), pitons – often called pins – could be removed or “cleaned” by the second climber while the leader remained at the highest point and belayed – held the rope in case the second slipped.

In the Robbins’ rule book, bolts were verboten.

In order to move over vast sections of rock absent any cracks where pins could be placed, a climber would sit in slings, and patiently and persistently, pound a drill bit into the rock face and then hammer an anchor with a hook into place. The climber could then attach his rope to this fixed anchor and, using slings around his feet, slowly ascend.

The ethical issues, as Robbins saw it: the process required brute force rather than skill and pounding bolts defaced the rock.

“[Robbins] climbing career over the next 20 years reads like a litany of all the most important ascents of the so-called golden age of climbing. He did the first ascent of the Northwest Face of Half Dome in 1956 and watched in horror as Warren Harding did the first ascent of El Capitan, spending 18 months laying siege to the wall with fixed ropes and 125 metal bolts drilled into the cliff. Harding finally finished the job with a 47-day push in 1958, after which Robbins did the second ascent in just seven days. It was an ascent so impressive, and so glaring in its contrast to Harding’s, that it served as a manifesto for the future of Yosemite rock climbing—declaring, in essence, that boldness and commitment and speed would forever count for more than engineering and logistics. …

“The competition between Robbins and Harding turned bitter for a while in the late 1960s, when Harding established the Dawn Wall route by drilling many hundreds of permanent metal bolts into the cliff. Robbins—like a self-appointed minister of righteousness—promptly repeated Harding’s Dawn Wall route with a hammer and cold chisel, chopping Harding’s bolts along the way as if to erase an abomination in the eyes of the mountain gods.

“That episode has gone down in climbing history as an ugly one, but it represents the essence of Robbins’s contribution to climbing today—an insistence that rules and ethics matter. In practical terms, that means always using whatever gear will cause the least possible damage to the rock. It means respecting the first ascent of a given climb as a work of art, such that later climbers never change the essential nature of the route by, say, adding new permanent safety hardware. Lastly, it means celebrating the constant push toward bolder and braver ways of climbing.”

Robbins calm and resolute approach to climbing was an inspiration to everyone that followed.

Comments

Leave a Comment

The ethics of rock climbers! Hey, we all have broken out New Years resolutions by now. It is appropriate and time for you to be excused from your promise for Lent…which was no more ethics discussions on the political scene….however, if you don’t go now, when you do, you’ll be looking at a mountain!