And it only took 529 years to solve this “cold case” of the… millennium!

According to a report in Nature (Dec. 2), DNA tests have confirmed that the skeletal remains found in a parking lot in Leicester, England in 2012, are, in fact, those of the infamous Richard III, the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty.

“Archaeological, osteological and radiocarbon dating data were consistent with these being his remains,” the report says. “We find a perfect mitochondrial DNA match between the sequence obtained from the remains and one living relative, and a single-base substitution when compared with a second relative. …

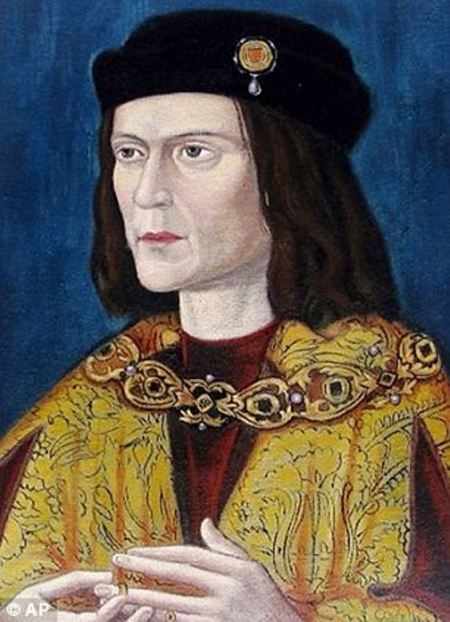

“DNA-predicted hair and eye colour are consistent with Richard’s appearance in an early portrait. We calculate likelihood ratios for the non-genetic and genetic data separately, and combined, and conclude that the evidence for the remains being those of Richard III is overwhelming.”

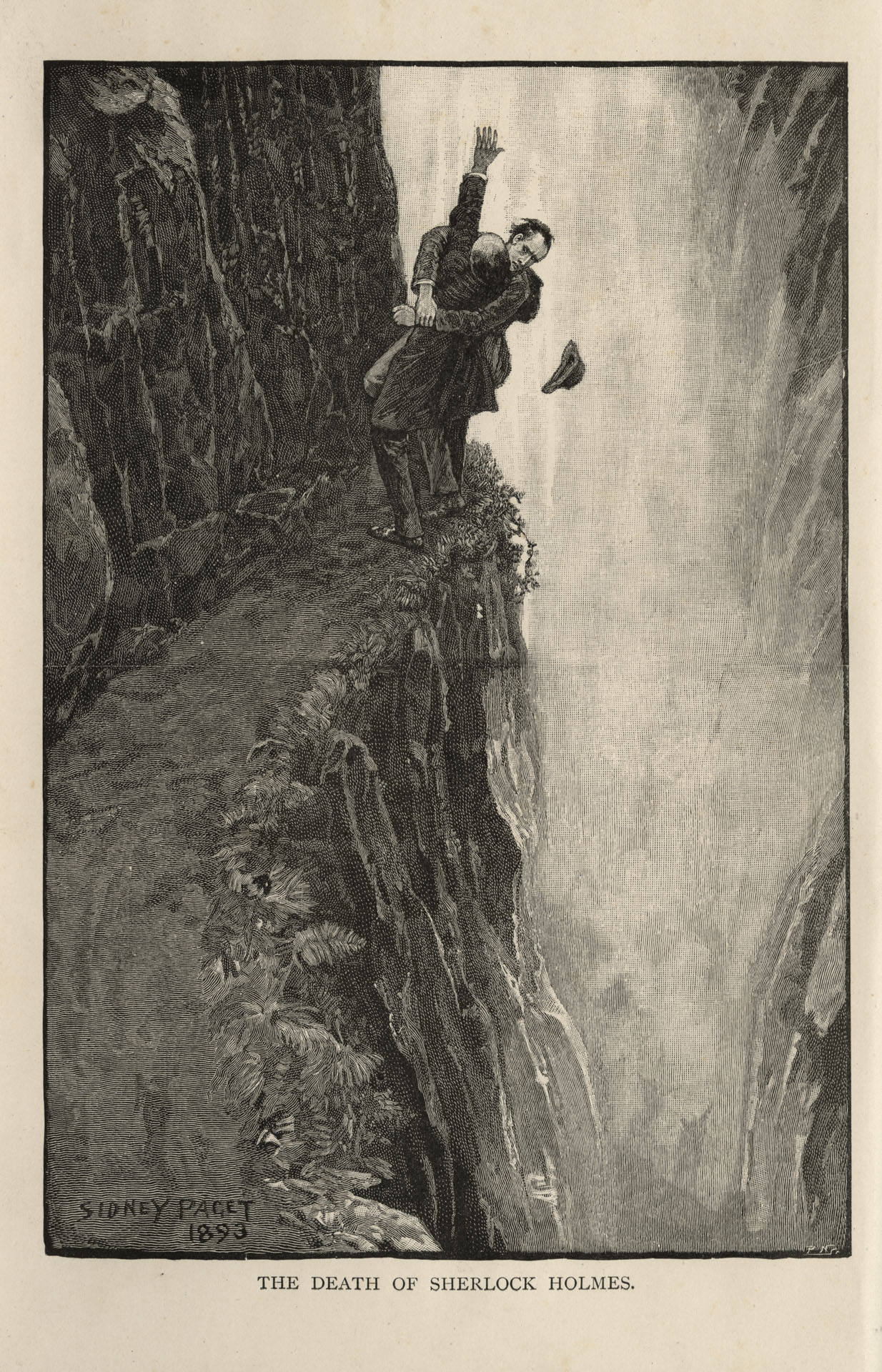

Richard III, one of Shakespeare’s most enduring plays, chiefly for the archetypal presentation of a villain most foul. However, the real Richard, who ascended the throne in 1483 following the death of his brother, Edward IV, led to the belief, as yet unproven, that along with lusting after Lady Anne, he murdered his two nephews to remove any obstacles to his title.

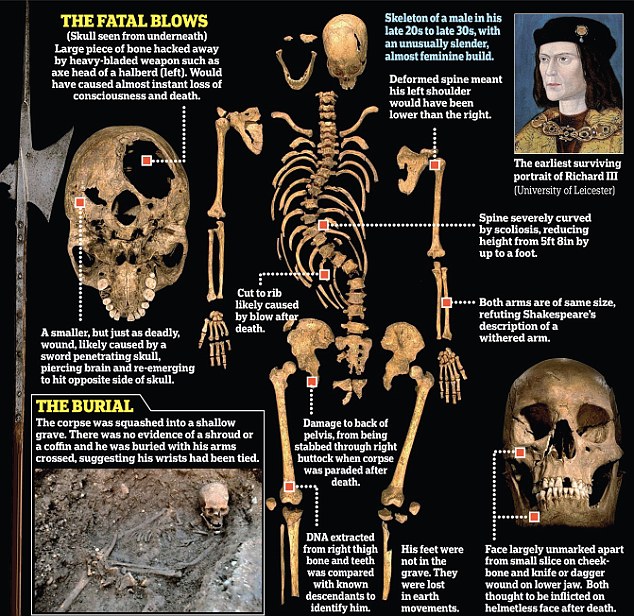

According to a story in Britain’s Daily Mail, (Feb. 4, 2013), “Academics were also able to reveal details of how one of the nation’s most controversial monarchs met his end – and how appallingly he was treated in death after defeat at the hands of Henry VII at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485.

“Stripped naked with his hands tied, and scarred by multiple ‘humiliation wounds’ inflicted as his body was paraded through Leicester, Richard III was dumped in a shallow grave with no coffin or shroud. There his body remained until his skeleton was discovered last year following a campaign led by Phillipa Langley, of the Richard III Society. Using historical maps, archaeologists had traced a friary where the king was rumoured to have been buried, which now lies beneath a social services department car park in Leicester.

“Screenwriter Miss Langley described the chill she felt when walking through the car park in August 2009: ‘It was a hot summer and I had goosebumps so badly and I was freezing cold.

“Only three weeks into the dig in September 2011, her instincts appeared to be confirmed when researchers found the skeleton of an adult male in a badly-dug grave who had a severely curved spine: Richard was famously nicknamed Crookback.

“The bones were subjected to ‘rigorous academic study’ by a team from the University of Leicester, and those involved were all sworn to secrecy until yesterday. Dig leader Richard Buckley said: ‘It is the academic conclusion that beyond reasonable doubt, the individual exhumed at Grey Friars is King Richard III – the last Plantagenet king of England.’

“The remains had lain almost completely undisturbed less than three feet below ground, but were almost destroyed when a 19th century outhouse was built just inches away.

“DNA from the skeleton was matched with two of Richard’s living descendants – Canadian-born furniture maker Michael Ibsen, whose mother was a direct descendant of the king’s sister Anne of York, and a second anonymous individual.

“The curved spine of the skeleton and its numerous wounds also helped confirm the ‘astonishing’ discovery, even if Richard’s so-called withered arm appears to be a myth.

“Studies revealed the remains dated back to the era of the War of the Roses, while the individual was found to be in his late 20s to 30s. Richard III was 32 when he died. His skeleton was found to have suffered ten injuries at the time of death, but only two skull wounds were potentially fatal and were most likely inflicted by a sword or a halberd – a spiked axe on a pole.”

According to folklore, Richard’s death was foretold by an old woman. In 1625 Sir Richard Baker wrote “upon this bridge stood a stone of some height; against which King Richard, as he passed toward Bosworth, by chance struck his spur; and against the same stone, as he was brought back, hanging by the horse-side, his head was dashed and broken: as a wise woman (forsooth) had foretold: who before his going to battle, being asked of his success, said, that where his spur struck, his head should be broken.”

In terms of Shakespeare’s character, Richard has become the embodiment of evil, but evil with a sympathetic side. Spark Notes, the study guide to the play points out that “In Act I, scene i, Richard dolefully claims that his malice toward others stems from the fact that he is unloved, and that he is unloved because of his physical deformity. This claim, which casts the other characters of the play as villains for punishing Richard for his appearance, makes it easy to sympathize with Richard during the first scenes of the play.”

However, from the beginning, Richard looks the audience square in the eyes and proclaims his evil in advance of his actions.

. . . since I cannot prove a lover

To entertain these fair well-spoken days,

I am determined to prove a villain

And hate the idle pleasures of these days.

But was the real Richard as evil as portrayed?

The National Geographic website contacted a historian. “Philip Shaw, a historical linguist at University of Leicester’s School of English, analyzed the only two know examples of Richard III’s own writing. Both are postscripts on letters otherwise composed by secretaries—one in 1469, before Richard became king, and one from 1483, the first year of his brief reign.

“In the 1469 letter, the 17-year-old seeks a loan of 100 pounds from the king’s under-treasurer. Although the request is clearly stated in the body of the letter, Richard adds an urgent P.S.: “I pray you that you fail me not now at this time in my great need, as you will that I show you my good lordship in that matter that you labour to me for.”

“That could either be a veiled threat (If you don’t lend me the money, I won’t do that thing you asked me to do) or friendly cajoling (Come on, I’m helping you out with something, so help me out with this loan).

“ ‘His decision to take the pen himself shows you how important that personal touch must have been in getting people to do something,’ Shaw said.

“The second letter, written to King Richard’s chancellor in 1483, also conveys a sense of urgency. He had just learned that the Duke of Buckingham—once a close ally—was leading a rebellion against him.

“ ‘He’s asking for his Great Seal to be sent to him so that he can use it to give out orders to suppress the rebellion,’ Shaw said. ‘He calls the Duke ‘the most untrue creature living.’ You get a sense of how personally let down and betrayed he feels.’

Shaw concludes his assessment with a final ethical rationalization for Richard’s actions: “He probably wasn’t quite the villain that Shakespeare portrays, though I suspect he was quite ruthless, but you probably couldn’t afford to be a very nice man if you wanted to survive as a king in those days.”

Comments